Psychology of War and Peace

Peace Psychology: Understanding Violence, Conflict, and the Pursuit of Sustainable Peace

Peace psychology is a specialized branch of psychology that focuses on the development of theories and practices aimed at preventing violence, managing conflict, and fostering sustainable peace. Rather than merely reacting to violence after it occurs, peace psychologists seek proactive approaches to reduce its root causes and to promote peaceful coexistence across cultures, nations, and communities.

Historical Origins and Foundational Thinkers

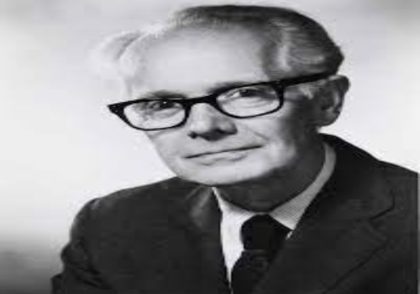

The intellectual foundations of peace psychology are often traced back to the American philosopher and psychologist William James, particularly his 1906 address at Stanford University. Anticipating the advent of World War I, James proposed that war fulfills certain deep human needs—such as loyalty, discipline, and social cohesion—that can also be met through morally equivalent nonviolent activities, such as organized public service. He believed that unless societies found a substitute for the emotional and moral experiences associated with war, they would continue to resort to armed conflict.

James’s ideas were later echoed and expanded upon by prominent thinkers, including Alfred Adler, Gordon Allport, Sigmund Freud, Mary Whiton Calkins, and Edward Tolman, among others. Some, such as Pythagoras, can even be considered early contributors to the field due to their advocacy for nonviolence and their recognition of structural violence—forms of harm embedded in social systems that deprive people of basic needs and human dignity.

War: Built, Not Born

A central tenet of peace psychology is that war is socially constructed, not biologically inevitable. While humans possess the capacity for aggression, war is not an unavoidable outcome of human nature. This idea was powerfully asserted in multiple peace manifestos over the 20th century, including one signed by nearly 4,000 psychologists following World War II and another in 1986 known as the Seville Statement, released during the United Nations International Year of Peace.

These declarations emphasized that the conditions leading to war—such as propaganda, social inequality, and structural injustice—can be scientifically studied and changed. Peace psychology thus prioritizes understanding the environmental and psychological factors that contribute to either violent behavior or peaceful action.

The Cold War and Institutional Growth

The discipline gained momentum during the Cold War era, when the looming threat of nuclear war between the United States and the Soviet Union heightened the urgency of understanding intergroup conflict. Psychologists began to explore how collective identities, stereotypes, and intergroup mistrust contribute to escalation, and how dialogue and empathy might serve as conflict-resolution tools.

In 1990, the American Psychological Association officially recognized peace psychology as a distinct division—Division 48—dedicated to the scientific study of peace and conflict. Shortly afterward, the field launched its own academic publication: Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology. Since then, peace psychology doctoral programs and research centers have emerged globally, with a growing emphasis on interdisciplinary collaboration and global justice.

Beyond War: Structural and Cultural Violence

Modern peace psychology recognizes that violence is not limited to the battlefield. It distinguishes among three interrelated forms of violence:

-

Direct violence: Physical harm or killing that is immediate and visible (e.g., warfare, assault).

-

Structural violence: Systemic harm caused by unequal access to resources, education, healthcare, or basic human needs. For instance, starvation in the presence of abundant food reflects structural failure in distribution systems.

-

Cultural violence: The use of ideologies or beliefs to justify either direct or structural violence. A classic example is blaming the victim—rationalizing poverty or hunger by attributing them to personal failure rather than systemic injustice.

One form of cultural violence is the just war theory, which posits that under certain moral conditions (e.g., self-defense, last resort), war and killing may be acceptable. Peace psychology critically examines such narratives and strives to offer nonviolent moral frameworks for addressing threats and injustices.

Peace Psychology in the Post-War Era

As the world continues to grapple with the legacies of war, genocide, displacement, and terrorism, peace psychology plays a vital role in shaping responses rooted in compassion, equity, and prevention. From post-conflict reconciliation efforts to trauma-informed education in war-torn areas, the field emphasizes restorative practices over retributive justice.

In today’s globalized context, peace psychology urges scholars and policymakers to address the structural and cultural roots of violence, particularly as they manifest in inequality, xenophobia, nationalism, and the securitization of everyday life. Preventing violence in the name of security—especially in the fight against terrorism—requires ethical and scientifically informed alternatives that go beyond military solutions.

References:

-

Christie, D. J., & Cooper, T. E. (contributing authors). Peace Psychology. In Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved from: https://www.britannica.com/science/peace-psychology

-

American Psychological Association (Division 48). Peace Psychology.

-

Seville Statement on Violence (1986). United Nations International Year of Peace.

This article is adapted and restructured from an original entry in Encyclopaedia Britannica:

Leave a Reply