Freud and Object Relations

Freud and Object Relations: The Foundational Starting Point

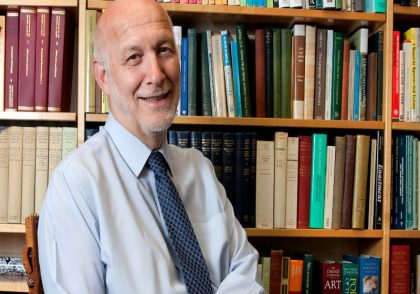

Sigmund Freud’s contributions to psychoanalysis laid the groundwork for later developments in object relations theory. Although Freud did not formulate object relations theory per se, many of its key assumptions—such as the significance of early relationships and internalized figures—can be traced to his writings. This article explores Freud’s relevance to object relations theory by examining core Freudian concepts, his perspective on relationships, the evolution of drive theory, and subsequent critiques.

Freud’s model of the psyche—consisting of the id, ego, and superego—reflects an internal world populated by conflicting mental forces (Freud, 1923). His drive theory initially emphasized the sexual (libidinal) and later the aggressive instincts as the primary motivational forces. These instincts, originating from within, sought gratification through objects in the external world. However, for Freud, the object was secondary to the aim of instinctual discharge (Freud, 1905/1953, p. 156).

Michael St. Clair emphasizes this point: “In classical Freudian theory, the object of the drive is not as important as the gratification of the drive itself” (St. Clair, 2004, p. 12). This object-usage model differs significantly from later theorists such as Melanie Klein or D.W. Winnicott, who placed relational needs at the center of development.

Freud’s conceptualization of object choice—especially his ideas around transference, identification, and internalization—laid the foundation for object relations thinking. For instance, in mourning and melancholia, the ego identifies with the lost object, incorporating aspects of it into the self (Freud, 1917/1957). This mechanism reflects a primitive form of internal object relations.

Critics argue that Freud underplayed the emotional and relational aspects of development, favoring a biologically driven model. Nonetheless, many core ideas of object relations—such as the internalization of significant others, the role of unconscious fantasies, and the persistence of early relationships in adult life—are embedded in Freud’s work, making him an indispensable starting point for understanding the evolution of psychoanalytic thought.

References:

– Freud, S. (1905/1953). Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality. SE, 7.

– Freud, S. (1917/1957). Mourning and Melancholia. SE, 14.

– Freud, S. (1923). The Ego and the Id. SE, 19.

– St. Clair, M. (2004). Object Relations and Self Psychology. Thomson Brooks/Cole.

Leave a Reply