Edith Jacobson and Object Relations Theory

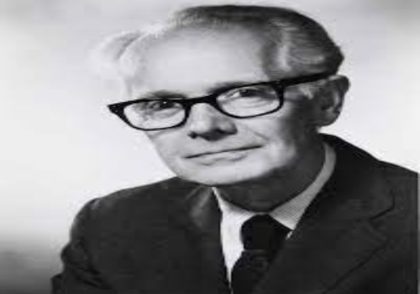

Biographical Background of Edith Jacobson

Edith Jacobson (1897–1978) was a German-American psychoanalyst and psychiatrist, whose significant theoretical contributions enriched the object relations tradition. She received her medical degree in Germany and trained psychoanalytically in Berlin during a period of great ferment in the psychoanalytic movement. Her work, both clinical and theoretical, took shape during the Nazi regime, which forced her into exile. She was imprisoned for a time due to her anti-fascist views, and after her release, she emigrated to the United States, where she continued her work at institutions like Chestnut Lodge and the Menninger Clinic.

Jacobson is best known for creating one of the most integrated models of the ego in psychoanalysis. Her ideas combined Freudian drive theory with ego psychology and object relations, producing a theoretical system that addressed both inner instinctual conflicts and interpersonal, relational processes. While her work is less popularly known than that of Melanie Klein or D. W. Winnicott—partly due to its abstract and dense conceptual style—Jacobson’s contributions deeply influenced theorists like Otto Kernberg and remain foundational in contemporary psychodynamic thinking.

Theoretical Position: Ego, Self, and Object Relations

Jacobson’s central concern was the development of the ego and its vicissitudes across normal and pathological development. In her magnum opus The Self and the Object World (1964), she advanced a nuanced theory of the ego as emerging from the interplay between internal drives and object relations, especially with the mother. For Jacobson, the ego is not merely a conflict moderator as in classical Freudian theory, but an evolving psychic structure shaped by affect-laden representations of the self and others.

She was among the first analysts to explicitly articulate the dynamic interrelation between the ego, self-representations, and object-representations. Drawing from both Freudian structural theory and ego psychology, she emphasized that internalized object relations form the building blocks of self-structure. Mental health, in her view, depends on the integration of positive and negative self- and object-representations, which are consolidated during early development.

Her emphasis on psychic structure placed her among ego psychologists, but her deep concern with unconscious fantasies, primitive anxieties, and developmental failures tied her firmly to the object relations tradition.

Self and Object Representations

A cornerstone of Jacobson’s theory lies in her concept of internal representations. The infant, through early affective experiences with caregivers—primarily the mother—develops psychic images of the self and the object. These are not static reflections, but dynamic internalized affective experiences. Over time, these representations become more differentiated and realistic, contributing to the development of a cohesive sense of identity.

She described how libidinal and aggressive drives become attached to these representations, which in turn influence the individual’s emotional reactions and interpersonal patterns. When this process proceeds in a healthy environment, the child can tolerate ambivalence and develop a differentiated, integrated self. But when early relationships are hostile, neglectful, or inconsistent, the self- and object-representations remain split or idealized/devalued, leading to vulnerability to disorders such as depression or borderline states.

Jacobson’s model of representation was among the first to propose that ego development and identity formation are inherently relational and structured by affect-laden internal objects.

Developmental Stages and the Formation of the Ego

Jacobson mapped ego development across a developmental timeline that intersects with both drive maturation and relational experience. Her model integrates the emergence of the ego from the id with the impact of object relations. In infancy, the self is merged with the object; differentiation of self and object occurs gradually and is fraught with anxiety, especially separation and annihilation anxieties.

She emphasized the role of mourning and depressive affect in normal development. Unlike the Kleinian emphasis on persecutory anxiety, Jacobson stressed the significance of loss, guilt, and depressive reactions as constructive forces in shaping the ego and superego. The ego matures by integrating painful realities, accepting limitations, and internalizing soothing objects that help modulate aggressive impulses.

This developmental perspective also accounts for the genesis of various psychopathologies. In depressive conditions, for example, Jacobson observed that aggressive drives become turned against the self when object loss or failure of soothing introjects destabilize the ego’s self-regulating functions (Jacobson, 1971).

Superego Formation

Edith Jacobson conducted perhaps the most comprehensive psychoanalytic study of the superego in the post-Freudian literature. She conceptualized the superego as emerging from three interrelated layers that function to regulate the child’s primitive sexual and destructive impulses and modulate the cathexis of libidinal and aggressive energy onto self-representations.

-

Primitive Punitive Images – The earliest layer of the superego consists of harsh and terrifying imagos, typically of parental figures. These representations are punitive and archaic, formed in response to early anxieties and fantasies of retaliation.

-

Ego Ideal – The second layer consists of the ego ideal: internalized standards and aspirations derived from admired or idealized caregivers. These ideals are partially ego-syntonic and serve a motivational function.

-

Modified and Realistic Identifications – The third, more mature layer includes identifications that are modulated, realistic, and less extreme. These allow the individual to integrate guilt, internalize norms, and maintain stable self-esteem.

Jacobson’s theory sees the superego not as a static entity, but as a dynamic regulatory structure, deeply intertwined with affect regulation, identity formation, and the quality of object relations (Jacobson, 1964; St. Clair, 2004).

Structure of the Psyche

While Jacobson retained the Freudian tripartite model of id, ego, and superego, she expanded its conceptual scope by integrating it with a relational approach. The ego was viewed as a synthesizing and reality-testing agency that grows in relation to both internal drive demands and external object constancy. The ego mediates between instinctual drives and affect-laden object relations, balancing impulses, defenses, and identifications.

Her view of psychic structure offered a bridge between instinct theory and object relations theory. Unlike Kleinians, who emphasized unconscious fantasy and innate drives, Jacobson emphasized the mediating and integrative capacities of the ego, shaped by both drive pressures and relational experiences.

Evaluation and Legacy

Jacobson’s work stands as a bridge between classical Freudian instinct theory and the relational turn in psychoanalysis. Her integrative model retains key Freudian concepts such as id, ego, and superego, while emphasizing how these psychic agencies emerge through complex interactions with internalized objects.

One of her most important contributions was her rigorous theorization of the self- and object-representations as building blocks of the psychic apparatus. Her developmental model of depression, based on the internalization of hostile or abandoning objects, has influenced the understanding of affective disorders far beyond psychoanalytic circles.

Nevertheless, her work has been criticized for its dense and abstract style, which made it less accessible than the writings of Melanie Klein, Fairbairn, or Winnicott. Moreover, her emphasis on inner structure sometimes downplayed the immediate clinical use of transference-countertransference dynamics, which became more prominent in later relational schools.

However, Edith Jacobson’s profound influence is undeniable, particularly in the work of Otto Kernberg. Kernberg’s model of borderline personality organization, with its focus on identity diffusion, splitting, and object-relations dyads, owes much to Jacobson’s theoretical foundations (Kernberg, 1975).

References

-

Jacobson, E. (1964). The Self and the Object World. New York: International Universities Press.

-

Jacobson, E. (1971). Depression: Comparative Studies of Normal, Neurotic, and Psychotic Conditions. New York: International Universities Press.

-

St. Clair, M. (2004). Object Relations and Self Psychology: An Introduction (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

-

Kernberg, O. F. (1975). Borderline Conditions and Pathological Narcissism. New York: Jason Aronson.

-

Mitchell, S. A., & Black, M. J. (1995). Freud and Beyond: A History of Modern Psychoanalytic Thought. New York: Basic Books

Leave a Reply