Carl Gustav Jung: Depth Psychology

Carl Gustav Jung: Depth Psychology, Individuation, and the Religious Imagination

Carl Gustav Jung: An Overview

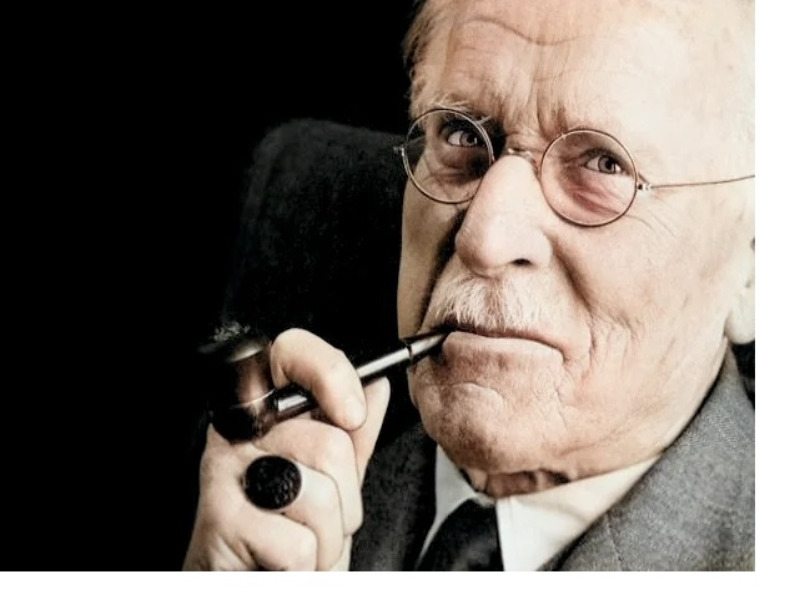

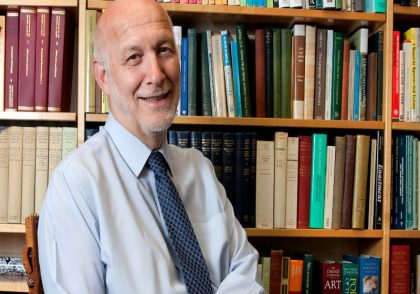

Carl Gustav Jung (1875–1961) was a Swiss psychiatrist and the founder of analytical psychology, a school of thought that diverged from Freudian psychoanalysis in its emphasis on the symbolic, mythological, and spiritual dimensions of the psyche. Best known for introducing the concepts of extraversion and introversion, the collective unconscious, and archetypes, Jung’s theories extended beyond clinical psychology into fields such as religious studies, literature, anthropology, and cultural criticism. His interdisciplinary vision and profound exploration of the human mind positioned him as one of the most original thinkers of the twentieth century.

Carl Jung’s break with classical psychoanalysis resulted not in a retreat from depth psychology but in its radical expansion. Whereas Freud emphasized the repressive functions of culture and the pathological roots of the unconscious, Jung turned toward symbolic expression, personal meaning, and the cultural embeddedness of the psyche. His interest in myth, religion, and dream symbolism led to a psychology that was not only therapeutic but also existential and philosophical. In this article, we examine the major elements of Jung’s thought and practice — the structure of the psyche, archetypal theory, psychotherapy, and his relationship with Freud — while also considering his relevance for contemporary psychological inquiry.

The Collective Unconscious and Archetypes

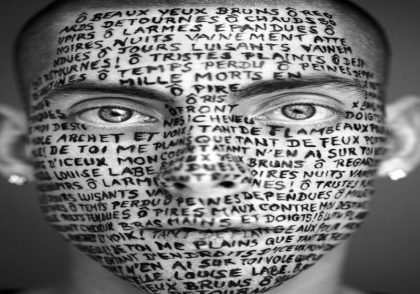

Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious is central to his psychological theory. It refers to a level of the unconscious that is shared among all humans and is composed of archetypes — innate, universal motifs and patterns that shape perception and experience. Unlike the personal unconscious, which is shaped by individual experience, the collective unconscious contains primordial images that appear across cultures in myths, fairy tales, religious symbols, and dreams (Jung, 1968).

These archetypes — such as the Hero, the Mother, the Trickster, and the Shadow — are not fixed symbols but dynamic forms that influence behavior, imagination, and development. They are often experienced during life transitions or crises, emerging in dreams or artistic expression. Jung saw these patterns as psychologically real and essential to understanding both mental suffering and psychological growth.

Persona, Shadow, and the Self

Jung proposed that the psyche is composed of multiple interacting systems: the ego (center of consciousness), the personal unconscious, and the collective unconscious. Within this framework, the persona is the mask or role one adopts in social life, while the shadow contains those parts of the self that are rejected, repressed, or morally condemned.

A core aim of Jungian analysis is to confront and integrate the shadow, allowing for greater psychological wholeness. This process ultimately leads toward the realization of the Self — a unifying center that transcends the ego. The journey toward the Self, which Jung termed individuation, is a central goal of his psychology. It entails becoming conscious of one’s unique inner life while integrating unconscious contents into a more cohesive and balanced personality (Jung, 1959).

Jung and Freud: Divergence and Dialogue

Carl Jung’s rise to international prominence in psychiatry naturally led him into intellectual alignment with Sigmund Freud. From 1907 to 1912, the two worked closely together, and Jung became one of Freud’s most trusted collaborators. He was even seen by many as Freud’s likely successor in the psychoanalytic movement, serving as the first president of the International Psychoanalytic Society in 1911 (Fordham & Fordham, 2024). However, significant theoretical tensions emerged.

While Jung initially supported many of Freud’s ideas, he grew increasingly uncomfortable with Freud’s insistence on the sexual origins of all neuroses. Their major rupture came in 1912 with the publication of Jung’s Wandlungen und Symbole der Libido (Psychology of the Unconscious, 1916), which reinterpreted libido not as narrowly sexual but as a generalized life energy. This work challenged key pillars of Freudian theory and marked the formal end of their collaboration. Jung resigned from the International Psychoanalytic Society in 1914.

Following the break, Jung turned inward. He began to explore the irrational aspects of his own psyche through self-analysis, documenting his inner visions, dreams, and fantasies — a process that laid the foundation for his concepts of the collective unconscious and archetypes. These ideas, he argued, were essential to understanding not only psychopathology but also mythology, religion, and human development (Jung, 1968).

Character of His Psychotherapy

Jung’s psychotherapeutic practice was deeply shaped by historical, symbolic, and religious dimensions. He emphasized that effective therapists should study classical literature, mystical writings, and the history of ideas, since patients’ dreams often echoed ancient myths or religious images (Fordham & Fordham, 2024). He viewed alchemy and Gnosticism as symbolic systems representing psychological transformation and spiritual maturation — systems that, though long forgotten by science, were psychologically alive.

He was particularly struck by the recurrence of alchemical imagery in patients’ fantasies and dreams, leading him to explore this tradition in four major volumes of his Collected Works (Jung, 1944). He believed that alchemists had unwittingly created a symbolic map of the unconscious, and that psychotherapy mirrored these same processes of purification, integration, and transformation.

Jung also pioneered psychotherapeutic work with middle-aged and elderly individuals. He noticed that many patients at this stage in life suffered not from repression but from a crisis of meaning. Many had lost their religious faith or personal direction. For Jung, helping them rediscover an inner myth — a guiding symbolic framework revealed through dream work and imagination — was key to psychological health. He called this individuation: the lifelong realization of the Self through conscious integration of the unconscious.

Jung and Religion: The Psychology of the Sacred

Unlike Freud, who regarded religion as a collective neurosis, Jung believed it served a crucial psychological function. Religious myths and rituals, he argued, were outward expressions of inner psychic processes. Christianity, Hinduism, Taoism, Gnosticism — all pointed to deep archetypal realities within the soul. He saw religious symbols not as dogma but as messages from the unconscious, offering healing and transformation (Jung, 1938; Jung & Wilhelm, 1962).

Jung’s appreciation for religion was not theological but psychological. He believed that modern individuals could engage religious symbols personally — not through belief but through direct inner experience. In this way, his psychology provided a bridge between the spiritual and the scientific.

Criticisms and Legacy

Despite his lasting influence, Jung’s work has been criticized for its speculative nature. Empirical psychologists have dismissed his ideas as unfalsifiable, while others have accused him of romanticizing mysticism. Feminist theorists have questioned the gendered nature of his archetypes, and some scholars have scrutinized his political positions in the 1930s, including the charge — now largely refuted — that he sympathized with Nazism (Shamdasani, 2003).

Yet Jung’s intellectual impact is undeniable. His work laid the foundation for depth psychology, archetypal analysis, art therapy, and religious psychology. He influenced thinkers as diverse as Joseph Campbell, Erich Neumann, James Hillman, and even contemporary neuroscience. Jungian terms such as introvert, extrovert, shadow, and synchronicity have entered everyday language, underscoring his cultural legacy.

Conclusion

Carl Gustav Jung’s vision of the psyche was rich, symbolic, and expansive. He dared to ask not only what causes suffering but what gives life meaning. His psychology called for a deeper engagement with myth, dream, and imagination — a path of individuation that placed the soul, not merely symptoms, at the center of healing. In a fragmented world, Jung’s call to wholeness and inner integration remains as vital as ever.

References

Fordham, M. S. M., & Fordham, F. (2024). Carl Gustav Jung: Biography. In Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Carl-Jung

Jung, C. G. (1913). The Theory of Psychoanalysis. London: Baillière, Tindall and Cox.

Jung, C. G. (1938). Psychology and Religion. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1944). Psychology and Alchemy. (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1959). Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self. (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1968). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (2009). The Red Book = Liber Novus. (S. Shamdasani, Ed.). New York: W. W. Norton.

Jung, C. G., & Wilhelm, R. (1962). The Secret of the Golden Flower. London: Routledge.

Shamdasani, S. (2003). Jung and the Making of Modern Psychology: The Dream of a Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Leave a Reply